Maybe they're concentrating on different kinds of sailing.

I'm sure in Hawaii's waves, there's a huge wind gradient, whereas in most speed sailing spots there's very little.

Maybe they're concentrating on different kinds of sailing.

I'm sure in Hawaii's waves, there's a huge wind gradient, whereas in most speed sailing spots there's very little.

They aren't talk about different kinds of sailing,they just have different opinion about how much wind gradient affects the sail and what is primary purpose of twist.

Yes, but could it just be from their perspective? If you're mainly making wave sails, then there is a bigger wind gradient effect.

It's interesting that there have been no contributions to this thread from current or recent past windsurfing sail designers. Is this because:

1. they don't frequent this blog or

2. They don't want to give away trade secrets or

3. They don't really understand themselves.

Windshear! You've gone off on another tack. I suppose Speed Raiders can tune twist for just one of the two, but the topic heading does include slalom.

Huh? ![]()

![]()

It's interesting that there have been no contributions to this thread from current or recent past windsurfing sail designers. Is this because:

1. they don't frequent this blog or

2. They don't want to give away trade secrets or

3. They don't really understand themselves.

Yes. ![]()

Windshear! You've gone off on another tack. I suppose Speed Raiders can tune twist for just one of the two, but the topic heading does include slalom.

Huh? ![]()

![]()

Back a bit now. The article USA46 referenced was about measuring shear (or twist ) in the true wind. Up to that point we were assuming the true wind had no twist and it was the apparent wind twisting. For big yachts this asymetry could be anticipated and allowed for by retrimming the "downhaul" on each tack.

But if the main reason for twist is something else then forget it.

My 2c worth... completely agree with Bruce Peterson.

Interesting that only you and decrepit write comment about David and Bruce explanation.

It leaves the impression that others don't care about their opinions.

My 2c worth... completely agree with Bruce Peterson.

Interesting that only you and decrepit write comment about David and Bruce explanation.

It leaves the impression that others don't care about their opinions.

Sorry, I missed the references.

It's interesting they have very different views re why twist works. I like BPs explanation.

I suspect that sailmakers use twist because testing proves it works and like us make educated guesses as to why it works

My 2c worth... completely agree with Bruce Peterson.

Interesting that only you and decrepit write comment about David and Bruce explanation.

It leaves the impression that others don't care about their opinions.

Well there's a challenge!

Reluctant to say too much about Bruce's blurb because he gets into a subject I don't know much about. Induced drag! Induced drag is the component of lift that's not perpendicular to your direction of travel. And tip vortices mess with the direction of air flowing over the wing. ( I'm well into my 10 minutes of mad googling now ). There's 3 ways of reducing tip vortices which basically amount to reducing the lift as you move towards the tip.

1. You can do it with plan form - the spitfire was famous for this,

2. reduce the thickness of the foil as you move out, or

3. include a bit of twist. Aeronautical folks call twist" washout". 1 to 2 degrees is about as much as they use.

But

www.pilotfriend.com/training/flight_training/aero/drag_red.htm

"Taper and twist are perhaps of greater importance in dealing with the problem of stalling."

Whereas Bruce says "Its primary purpose is to reduce the profile and induced drag that is a byproduct of generating aerodynamic lift."

It's Bruce vs. the aeronautical engineers.

Profile drag ?

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasitic_drag

"Profile drag is usually defined as the sum of form drag and skin friction.[1] However, the term is often used synonymously with form drag."

My first thought is that profile drag would be reduced by getting rid of that floppy loose leech.

"Pairwise flow " what does that mean? Google is no help.

His comments on lowering the centre of effort seem fair and reasonable. We were all thinking that anyway.

"There is very little wind gradient over height of a windsurfing sail, so gradient is not much of a factor./Bruce"

Even if it takes minutes for this wind gradient to become apparent there is no harm in allowing for the average. I did the trigonometry once, pulled a log profile out of the hat, put in typical windsurfing speeds and figured it only accounts for about one third of the twist that sails are using. Maybe I should recheck my calcs but I agree with Bruce on that one.

David Ezzy passes the google test. Doesn't say anything controversial. He makes an interesting point about stability. Along the lines of the aeronautical stability imparted by washout. The lower part of the sail will stall first. Then as we sheet in looking for balance, the top will move to its most efficient lifting angle , and with all that leverage will compensate for the loss down low keeping us balanced. How often do we over sheet the bottom of the sail? Maybe more often than we think?

Whereas Bruce says "Its primary purpose is to reduce the profile and induced drag that is a byproduct of generating aerodynamic lift."

Profile drag ?

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasitic_drag

"Profile drag is usually defined as the sum of form drag and skin friction.[1] However, the term is often used synonymously with form drag."

My first thought is that profile drag would be reduced by getting rid of that floppy loose leech.

"Its primary purpose is to reduce the profile and induced drag that is a byproduct of generating aerodynamic lift."

Profile drag ?

I dont know did he mean on reduce sail profile or profile drag,but twist will do both.

If he mean on profile drag wouldn't word "is a byproduct" in his sentence must be in plural(are byproducts)?

First time when I read his text I think he mean on reducing sail profile in upper part..

If you have loose leech,upper part of sail twist,high pressure on windward side is reduced battens are less bent,so profile in this area has less curve/belly.

In windsurfing they use term "profile" to tell how much camber(belly for average peopel) has sail.

You can often hear someone say "sail has more profile in lower part",that mean it has more camber/curve(belly) in lower part..

If leech is tight,high windward pressure will bent battens ,sail will have more "belly" which will significantly increase lift in upper part ,COE will move up and you will be catapult or out of balance all the time...

If he mean on profile drag,this is correct.Profile drag often used for form/pressure drag.

Twist aligned sail more close to apparent wind,now wind "hits" sail at smaller angle, logical form drag drop.

Just like when keep hand out of window in driving car,if hand is aligned with wind you feel small drag but if you rotate hand on some angle in relation to wind ,you will feel huge form drag,

Two more reasons why windsurfing sail must has so much twist are rake and taper ,because they cause lots of "upwash" effect.

****Just one note before start,term upwash come from aircraft terminology,wing on aircraft stay horizontal so they call this air movement upwash.Our sails stay vertical so just shift in our orientation where upwash become sidewash,upward become sideward motion,top of airfoil =leeward side of sail, outboard wing=upper part of sail,etc...easy

"Upwash"

An airfoil developing lift causes the flow approaching it to bend upward. This is because the lower pressure on top of the airfoil pulls air up toward it. This upward change in flow angle is called upwash

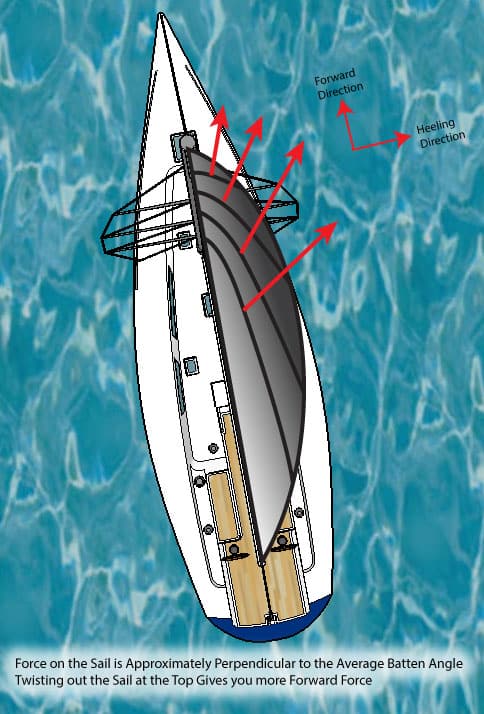

In windsurifng sail "upwash" will shift apparent wind in upper parts of sail so you must have twist to adapat sail AoA to different apparent wind direction.

Rake

Rake has the effect of increasing the upwash on the outboard wing sections. As a wing is angled aft, flow over the outboard sections must pass by the low pressure on top of the wing sections immediately inboard and forward. The close proximity of that low pressure to the air just outboard causes the outboard flow to turn upward more, resulting in higher upwash on the outboard wing.

Taper (wide foot to narrow head)

A tapered wing has a much shorter tip section than root section. As the wing tapers, lift produced by the shorter outboard sections is less because they have less surface area to support lift. Since the outboard sections are smaller than the inboard sections, they are significantly influenced by the larger wing just inboard. Air approaching the outboard portion of the wing is deflected by the low pressure on top of the larger inboard wing that is still generating a large amount of lift only a short distance away. The close proximity of that low pressure to the outboard wing causes the flow to be pulled upward additionally over the outboard wing. Hence, the smaller outboard sections operate with higher upwash.

shift in apparent wind direction in upper parts of sail because of "upwash" effect

It leaves the impression that others don't care about their opinions.

Yep. Dont much care about opinions alone. They sound very much like the theories we all have.

Care about evidence to back up opinions. None was given, so nothing to really comment on.

So, you have given us some theories on UPWASH, RAKE and TAPER. You speak of this as if it is well researched and docmented with evidence.

If that is the case, show us the evidence. Where are the papers you quote? Pictures from wind tunnel tests etc.

Dont get me wrong. We very much appreciate your input. ![]()

I think some of the explanations from air plane wings only add confusion. For airplanes, the term "apparent wind" is largely pointless, since the planes are traveling at a speed that is substantially higher than the wind speed. In flight, apparent wind is totally dominated by induced wind. That is very different from windsurfing, where the true wind and induced wind components of the apparent wind are very similar.

The other big difference is that the apparent wind for an air plane wing does not change over the length of the wing. For windsurfing, we can certainly assume that the true wind near the bottom of the sail is much less than at the top of the sail, while the induced wind is the same. So both angle and magnitude of the apparent wind will change vertically. How much is the interesting question, and how this relates to sail twist.

On a beam reach, the apparent wind angle will change by about 16 degrees when the true wind drops to 50% (assuming board speeds of 50% above wind speed). The maximum change, for a true wind speed drop to 0, would be 34 degrees. I'd guess the actual twist for race sails is probably somewhere around 30-40degrees - but that's between the top and the boom, and we definitely still have some wind at the boom!

So the twist seems to be larger than what would be needed for any change in wind speed. Watching the PWA sailors in France right now, the very top of the sails seem fully depowered. We also don't have any profile in the top section of the sail - so it seems that Bruce Peterson's explanation would be correct, even if his statement that "There is very little wind gradient over height of a windsurfing sail" were to be incorrect.

One way of looking at what the very loose part of the sail near the top does is that is simply prevents the air from going to the other side, thereby killing drag-producing vortices before they start.

It leaves the impression that others don't care about their opinions.

Yep. Dont much care about opinions alone. They sound very much like the theories we all have.

Care about evidence to back up opinions. None was given, so nothing to really comment on.

So, you have given us some theories on UPWASH, RAKE and TAPER. You speak of this as if it is well researched and docmented with evidence.

If that is the case, show us the evidence. Where are the papers you quote? Pictures from wind tunnel tests etc.

Dont get me wrong. We very much appreciate your input. ![]()

Text about UPWASH,RAKE,TAPER is quote from Paul Bogataj aeronautical engineer, specializing in sailing applications. He was responsible for appendage development for Team Dennis Conner and Young America in the 1995 and 2000 America's Cups, respectively. He approaches sail and keel design from the perspective of using advanced aerodynamic technology and methods that have been developed for the aircraft industry. He previously worked for Boeing, but currently consults independently for a variety of sailing design projects.

He has employed his knowledge of how sailboats function to win the North American Championship of two different classes, and numerous fleet and district championships. Paul combines his practical understanding of sailing from his experience as a successful racing sailor with his awareness of fluid dynamic principles as an engineer to provide explanations of how sailboats work that are understandable to the average sailor.

link:

www.northsails.com/sailing/en/2016/09/how-sails-work

I am waiting for wind,my "tool" will show if telltales will be at different angles from 0-6 meters.

telltales are from wool,they are so light so it is easier to test on light wind.

simple & cheap

The plan is test in 3 courses,upwind(40deg),crossswind(90) and deep downwind(140-150) also with different boat speed.Max boat speed is 45knots so I cant test in records speed 50kt+

I doubt there will be shift in apparent wind direction on flat water..Maybe I am wrong..

Text about UPWASH,RAKE,TAPER is quote from Paul Bogataj aeronautical engineer, specializing in sailing applications. He was responsible for appendage development for Team Dennis Conner and Young America in the 1995 and 2000 America's Cups, respectively. He approaches sail and keel design from the perspective of using advanced aerodynamic technology and methods that have been developed for the aircraft industry. He previously worked for Boeing, but currently consults independently for a variety of sailing design projects.

He has employed his knowledge of how sailboats function to win the North American Championship of two different classes, and numerous fleet and district championships. Paul combines his practical understanding of sailing from his experience as a successful racing sailor with his awareness of fluid dynamic principles as an engineer to provide explanations of how sailboats work that are understandable to the average sailor.

link:

www.northsails.com/sailing/en/2016/09/how-sails-work

I am waiting for wind,my "tool" will show if telltales will be at different angles from 0-6 meters.

telltales are from wool,they are so light so it is easier to test on light wind.

simple & cheap

The plan is test in 3 courses,upwind(40deg),crossswind(90) and deep downwind(140-150) also with different boat speed.Max boat speed is 45knots so I cant test in records speed 50kt+

I doubt there will be shift in apparent wind direction on flat water..Maybe I am wrong..

Ah, Thanks for that find. ![]() Quite a nicely written article. Now I will have to do some research to find the research to back that up.

Quite a nicely written article. Now I will have to do some research to find the research to back that up. ![]()

Good on you for doing that experiment. I think you will have some problems finding a place to do the 45 knots run in 40+ knots of wind at 140 off the wind ![]()

If you can find a place to drive at 40 in 25-30 knots it would be very representative. And if you find that spot, you have also found a really good speed course. ![]() I assume from your usernane that you are in the USA, a place that seems not very well endowed with discovered 'speed' spots. I'm sure they muct be there, but i assume that not many people are looking for them.?

I assume from your usernane that you are in the USA, a place that seems not very well endowed with discovered 'speed' spots. I'm sure they muct be there, but i assume that not many people are looking for them.?

Found this excerpt that seems to back up our feeling that vind velocity change at height can vary:

From: websites.pmc.ucsc.edu/~jnoble/wind/extrap/

"In practice, it has been found that ? varies with such parameters as elevation, time of day, season, temperature, terrain, and atmospheric stability. The larger the exponent the larger the vertical gradient in the wind speed. Although the power law is a useful engineering approximation of the average wind speed profile, actual profiles will deviate from this relationship."

I'm finding it hard to actually find actual experimental data on this at heights relevant to us..

Observation data from: www.ep.liu.se/ecp/057/vol15/005/ecp57vol15_005.pdf

Wind shear decreases dramatically day v's night:

Take away: Go faster in daylight. ![]() .

.

But, average wind speed was much lower during the night.

As wind speed increase, the turbulence decreased. Our typical speed sailing range is 15m/s to 20 m/s (30-40 knots):

If turbulence is directly coupled with wind shear, one would expect a corresponding decrease in wind shear over height in stronger winds over a relatively smooth surface.

If turbulence is directly coupled with wind shear, one would expect a corresponding decrease in wind shear over height in stronger winds over a relatively smooth surface.

And that is eactly what we see here:

The problem for us is that these measurements were taken from 10-40 m aboube ground level, and probably on a rougher land surface than a typical speed spot (Luderitz excluded), and also at mean wind speeds much lower than we typically sail in by a large factor.

It may not be unreasonable though, to assume the relationship is at least representative of stronger winds and smaller height scale over a smoother surface. More research needed by me I think. ![]()

I think this is the paper that Ian quoted earlier:www.onemetre.net/Design/Gradient/Gradient.htm

My problem with those graphs is that they are for wind speeds up to only around 5m/sec.(10 knots) This probably has more relevance for light wind windsurfing and foiling.

from wikipedia: Braithwaite says: the wind gradient is not significant for sailboats when the wind is over 6 knots (because a wind speed of 10 knots at the surface corresponds to 15 knots at 300 meters, so the change in speed is negligible over the height of a sailboat's mast). According to the same source, the wind increases steadily with height up to about 10 meters in 5 knot winds but less if there is less wind. That source states that in winds with average speeds of six knots or more, the change of speed with height is confined almost entirely to the one or two meters closest to the surface.

This is consistent with another source, which shows that the change in wind speed is very small for heights over 2 meters[40] and with a statement by the Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology[41] according to which: differences can be as little as 5% in unstable air

One could quite easily test this with a few identical recording anemometers attached to a 4m pole, but I dont personally have the 3 ot 4 identical anemometers required, and mine dont have a recording function anyhow. If someone can find a relitively inexpensive source of such devices, I would be interested in pursuing this line.

But I think it is something we dont really need to do. It seems to me that there seems to be enough evidence that over a smooth surface, wind gradient is negligible in strong winds from over around 1 meter, possibly even lower in some situations relevant to speed sailing.

Neverthless, next time we have a 30 Knots SW, I will see if I can get a sense of this using a single anemometer held for resonable periods at various heights above the sand on the beach to the windward side of the Sandy Point spit. It strikes me that another good place to test like this would be at Cockies, Lake George, on a steady SE summer 30kt wind, like the one I have described before where at head level, I found the wind speed varying by mostly less than 2 knots, around the 30 knots mark, for long periods of observation. This is very stable wind coming off the ocean about 10Km away, over low dunes on the coastline for a very short distance, and then over a very flat lake (with almost no waves because of the weed - less than 10-15cm) for at least 6km.

In any case, it appears that Bruce's statement is probably pretty accurate. That is, we dont need sail twist to account for wind gradient. ![]()

Now to move on the the other things that USA46 brought up. Rake, Taper and Upwash ![]()

This section from the document quoted above: "How sails work - north sails", seems to suggest that flattening and twisting the top of a sail, while lowering the CoE and reducing heeling moment, will also increase induced drag, not decrease it as some of us have speculated.![]()

Setting Sail

Recognize that the objective of the sails is to create force to pull the boat, but that there can also be a constraint on heel. At some point the stability of the boat or weight of the crew cannot keep the boat sailing at an angle that does not compromise performance, so just using the sails to produce the most force possible is not necessarily the fastest procedure.In lighter winds, when the sails are struggling to extract enough force from the wind to move the boat fast, the sails should be set such that every section along the height of the sail is working to produce high lift, especially the top sections in order to minimize induced drag. When the wind builds beyond a level that the sails' force causes the boat to heel too much, the sails' characteristics must be modified. There are several options.Reducing the amount of camber in the entire sail will decrease the amount of force the sail produces, as will decreasing the angle of attack of the entire sail. Implementing these adjustments over the entire sail may or may not be the best alternative for the windier conditions.

They reduce the amount of force generated by the sail, but that force is still centered at a similar height. In order to reduce the heeling moment created by the sails to a satisfactory level, the amount of force may decrease to a level that does not pull the boat very fast anymore.Another approach is to reduce the lift produced by the top of the sail. Reducing the camber of the top of the sail, and/or reducing the angle of attack of the top of the sail through additional twist will affect the sail's force such that the remaining force is centered lower down. similar reduction in heeling moment as simply reducing the entire sail's force can be achieved through depowering the top of the sail, but while maintaining more total force to pull the boat. The force is centered lower as the bottom of the sail still trimmed in a fashion that generates substantial lift. This method has the compromise of deviating further from the desired elliptical spanload, as the lift distribution diminishes much more rapidly toward the top of the sail, and causes higher induced drag. The question becomes whether the remaining higher sail force offsets the additional drag component.A parallel situation occurs with airplanes. Airplanes are not designed to fly with the optimal spanload that yields minimum induced drag because the higher outboard load on the wing would require that the wing be made stronger, hence heavier, to carry that load. It is more efficient to build the airplane lighter and generate more lift on the inboard wing and accept a little more induced drag. This is the same tradeoff that a sailboat experiences in strong wind when heeling becomes a factor and results in a similar, less than optimal spanload in order to maximize performance.

That's confirmed in wikipeadia.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Log_wind_profile

"The log wind profile is generally considered to be a more reliable estimator of mean wind speed than the wind profile power law in the lowest 10-20 m of the planetary boundary layer. Between 20 m and 100 m both methods can produce reasonable predictions of mean wind speed in neutral atmospheric conditions. From 100 m to near the top of the atmospheric boundary layer the power law produces more accurate predictions of mean wind speed (assuming neutral atmospheric conditions).[3]

The neutral atmospheric stability assumption discussed above is reasonable when the hourly mean wind speed at a height of 10 m exceeds 10 m/s where turbulent mixing overpowers atmospheric instability.[3]"

So sailing in wind getting toward 20 knots we shouldn't expect the strange effects due to stratification that big boat sailors out in only 5 knots report. The logarithmic profiles without the stability term don't show that much change between 1 and 4 metres.

This section from the document quoted above: "How sails work - north sails", seems to suggest that flattening and twisting the top of a sail, while lowering the CoE and reducing heeling moment, will also increase induced drag, not decrease it as some of us have speculated.![]()

Setting Sail

Recognize that the objective of the sails is to create force to pull the boat, but that there can also be a constraint on heel. At some point the stability of the boat or weight of the crew cannot keep the boat sailing at an angle that does not compromise performance, so just using the sails to produce the most force possible is not necessarily the fastest procedure.In lighter winds, when the sails are struggling to extract enough force from the wind to move the boat fast, the sails should be set such that every section along the height of the sail is working to produce high lift, especially the top sections in order to minimize induced drag. When the wind builds beyond a level that the sails' force causes the boat to heel too much, the sails' characteristics must be modified. There are several options.Reducing the amount of camber in the entire sail will decrease the amount of force the sail produces, as will decreasing the angle of attack of the entire sail. Implementing these adjustments over the entire sail may or may not be the best alternative for the windier conditions.

They reduce the amount of force generated by the sail, but that force is still centered at a similar height. In order to reduce the heeling moment created by the sails to a satisfactory level, the amount of force may decrease to a level that does not pull the boat very fast anymore.Another approach is to reduce the lift produced by the top of the sail. Reducing the camber of the top of the sail, and/or reducing the angle of attack of the top of the sail through additional twist will affect the sail's force such that the remaining force is centered lower down. similar reduction in heeling moment as simply reducing the entire sail's force can be achieved through depowering the top of the sail, but while maintaining more total force to pull the boat. The force is centered lower as the bottom of the sail still trimmed in a fashion that generates substantial lift. This method has the compromise of deviating further from the desired elliptical spanload, as the lift distribution diminishes much more rapidly toward the top of the sail, and causes higher induced drag. The question becomes whether the remaining higher sail force offsets the additional drag component.A parallel situation occurs with airplanes. Airplanes are not designed to fly with the optimal spanload that yields minimum induced drag because the higher outboard load on the wing would require that the wing be made stronger, hence heavier, to carry that load. It is more efficient to build the airplane lighter and generate more lift on the inboard wing and accept a little more induced drag. This is the same tradeoff that a sailboat experiences in strong wind when heeling becomes a factor and results in a similar, less than optimal spanload in order to maximize performance.

I was thinking will I post this link or not, because I knew that this old theory is inside text.I hope no one will read all text.

Sailquik you are now open new most complicated topic "ELIPTICAL VS BELL spanload distribution"

Author assumption is that eliptical spanload has minimum induce drag.

If you want have eliptical spanload ,head must produce lift, so this is his logic.

Problem is that eliptical spanload has minimum drag only if wingspan is limitation.

In other situation bell spanlod is more efficient.

It is very complicated topic and you must have good aerodynamic knowledge to understand this.

Nasa spend milions of dollars to research "new" bell spanload distribution in order to find minimum drag.

Al Bowers Nasa engineer is cheef of this expedition,everything start when he start watching birds wings with bell spanload which have milions of years of evolution.He try to solve problem with "adwerse yaw" without rudder,birds dont have rudder,then he find this phenomen,

Concept name is PRANDTL wing (Preliminary Research Aerodynamic Design To Lower Drag PRANDTL)

link:

ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20160003578.pdf

bell spanload is also present at HECS wings, where test seagull wing cofiguration,

link:

ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20060045566.pdf

Optimum sail twist is a function of board speed to wind speed ratio (aka Foehn Number; Kenney 2001). When hyperwind sailing at high Foehn Numbers, the optimum twist is zero.

Windsurfers are not very efficient and generally sail at less than Foehn Number 1.5. The optimum sail twist with height for a windsurfer can be calculated if both the board speed and wind gradient (increase in wind speed with height) are measured. Alternatively, a typical spanwise sail twist distribution can be calculated for a typical board speed and typical wind gradient in order to get a feeling for the order of magnitude of optimum twist (i.e. how much twist is too much).

Here is some hyperwind sailing data collected while out for an afternoon sail; not a speed trial.

Conditions:

- light winds typically 8 to 10 knots; 10 knots was used as input to the numerical model computing the maximum speed polars (blue lines on the polar plot)

Results: plotted with GPSResults

- 3.4 sq m sail; ZERO twist; ZERO camber

- GT-31 gps speed data are the red circles on the polar plot

- max speed measured was 37 knots

Ref: Kenney, B.C., 2001. Hyperwind Sailing, Catalyst, J. Am. Yacht Res. Soc., 6, 24-26.

This method has the compromise of deviating further from the desired elliptical spanload, as the lift distribution diminishes much more rapidly toward the top of the sail, and causes higher induced drag. The question becomes whether the remaining higher sail force offsets the additional drag component.A parallel situation occurs with airplanes. Airplanes are not designed to fly with the optimal spanload that yields minimum induced drag because the higher outboard load on the wing would require that the wing be made stronger, hence heavier, to carry that load. It is more efficient to build the airplane lighter and generate more lift on the inboard wing and accept a little more induced drag. This is the same tradeoff that a sailboat experiences in strong wind when heeling becomes a factor and results in a similar, less than optimal spanload in order to maximize performance.

quote from my first link:

"In 1922 Ludwig Prandtl published his "lifting line" theory in English; the tool enabled the calculation of lift and drag for a given wing. Using this tool results in the optimum spanload for minimum induced drag (the greatest efficiency) for a given span, which, Prandtl said, was elliptical (ref. 1). Since then, the lifting line theory and elliptical spanload have become the standard design tool and wing spanloading in aviation. So ubiquitous is it that avian researchers have relied on it to explain bird flight data almost since its introduction. But in 1933 Prandtl published a second paper on the subject in which he conceded that his first conclusion was incomplete: there was a superior spanload solution to maximum efficiency for a given structural weight. "That the wingspan has to be specified," he wrote, "leads to the invalid assertion that the elliptical distribution is best" (ref. 2). His new bell-shaped spanload creates a wing that is 11 percent more efficient and has 22 percent greater span than its elliptically-loaded cousin, all while using exactly the same amount of structure. It results in the minimum drag solution in every case of physical wings: any other solution will produce greater drag. Oddly, Prandtl's second spanload remains virtually unknown. "

Instead read/ watch all my links and videos in previous post,I will try explain with example.

If we have sail wich must support 100kg sailor ,we have two solution:

a) 3.8m high sail with eliptical spanload (head must produce lift,in order to do this leech must be tight)

or

b)4.6m high sail with bell spanload (max lift in lower parts,loose leech, floppy head to unload tip)

solution b) will has 22% greater height and 11% better efficiency (lift/drag ratio)

red line= eliptical spanload

blue line=bell spanload (max lift in lower part,floppy head reduce lift to zero before tip (4.6m) )